Place matters. Despite the allure of the ‘here’ and ‘there’, ‘anytime’, anywhere’ phenomenon people feel the need to be grounded and for some things to be constant. They want to belong and to identify with a group of people, they seek the familiar and known, the stable, predictable as well as the chance for change and choice. It is ironic that even the rootless and the restless, the hyper mobile find respite in friendly certainties.

A sense of anchorage fits our desire for a place we can call home, to which we have commitment and loyalty. Good places provide this sense of a past, history, things we value and traditions that feel alive and not claustrophobic - mutable, adaptable and open. This is not about nostalgia, but understanding well how vibrancy and progress rely on understanding what went before and building on that.

Commitment to place engenders the kind of pride that encourages people to give back and to take responsibility for their city. This expresses itself in many forms: civic engagement, volunteering and philanthropy, respecting the best heritage, cherishing the distinctive, business pledging itself to public interest objectives, even feeling a sense of duty to the well-being of your city.

A sense of place is created through time. It imbues the fabric of buildings, streets, the urban pattern with its layers of history which at their best can be evocative. It includes cultural activities, special rituals and the way the city goes about its business of life. It involves invisible things in our mind: memories, our knowledge of the city’s background, its famous people, events and the products and resources it is known for, its reputation and global resonance.

Creating this sense of place afresh is not easy. It requires acute observation, heightened sensibilities, emotional sophistication and good design, as well as knowing when to keep the best and when to reinvent the rest. Here ambitious programming can help to tap into the city’s energy and motivations with the aim of enriching that sense of belonging and identity.

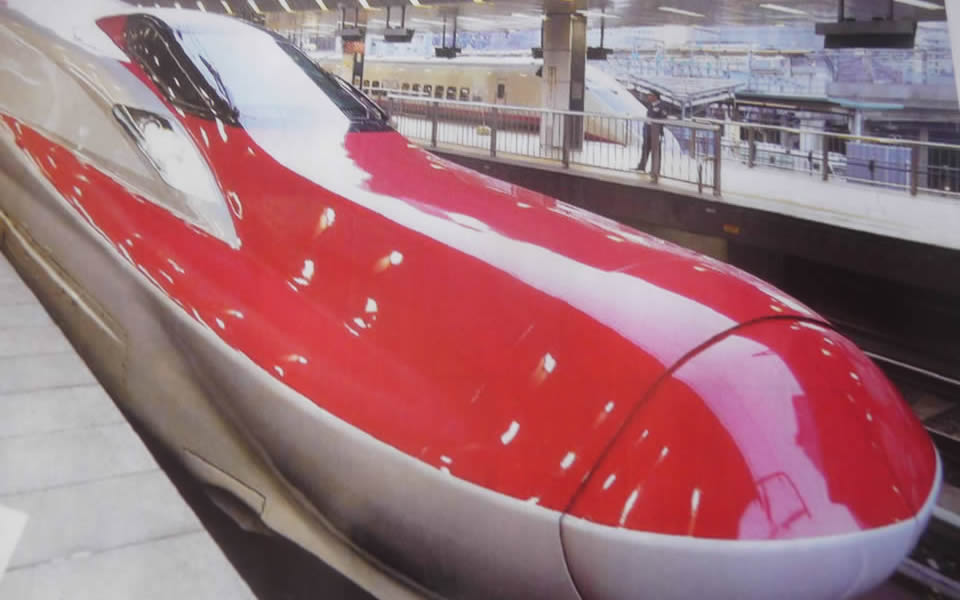

Cities are places where people meet, talk, interact and trade. We connect, communicate, converse and exchange. In the city most of us are strangers to each other, while in the village everyone is known and in the town many people are familiar. Urban vitality evolves when communications work well: face- to- face, physically and virtually. It needs gathering places that encourage conversation and transactions. It needs mobility systems that seamlessly connect people in the city itself and further afield and are easy to use. It needs ubiquitous wifi. These enhance its networking capacity and so the city becomes an accelerator of opportunities.

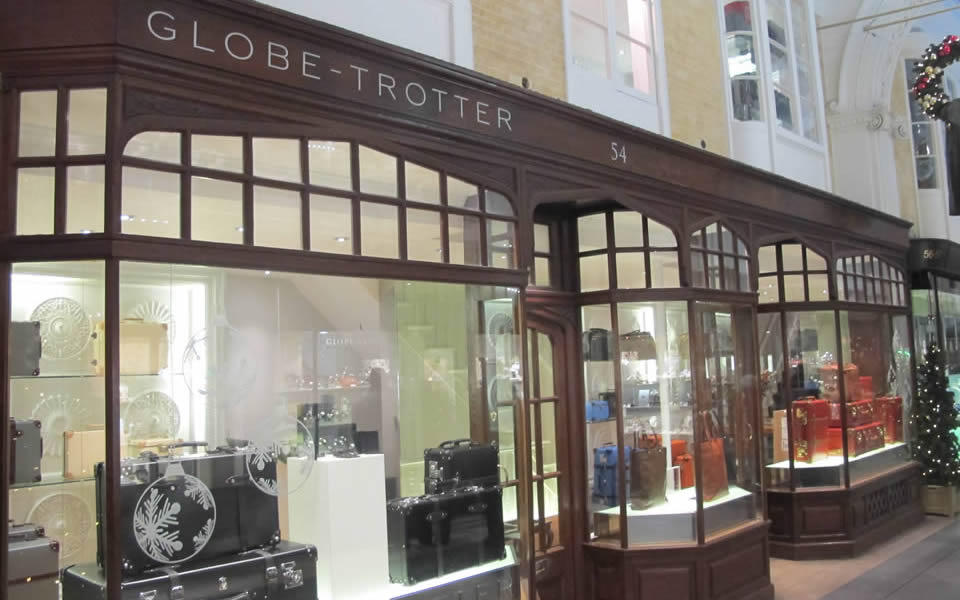

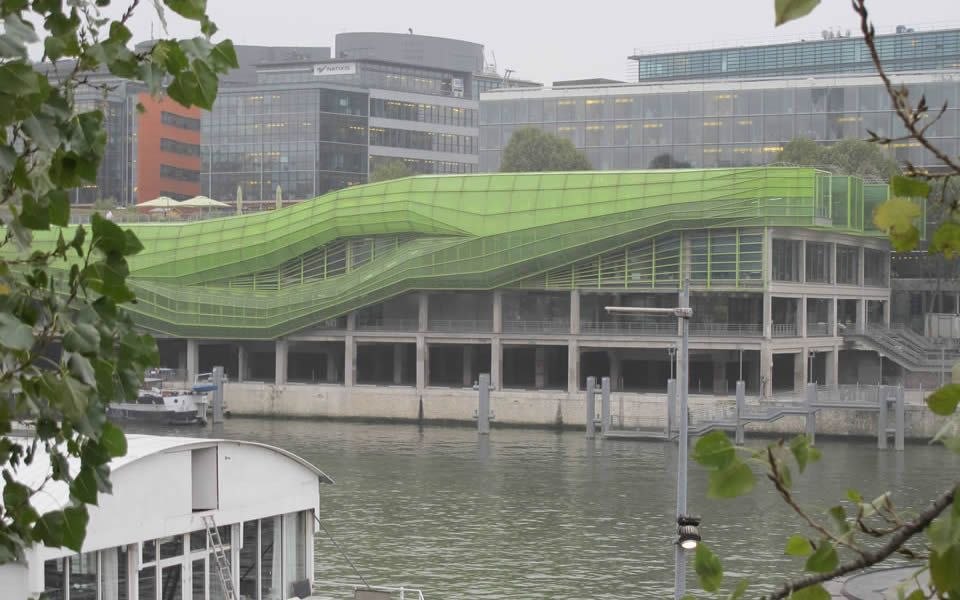

Good design and the visual landscape aids communication as does appreciating the sensory experience of places since the city communicates through every fibre of its being. The aesthetic qualities of buildings are crucial as are the overall layout of streets, neighbourhoods, public space, parks, signage, advertising, urban furniture. The same goes for the appearance of trains, buses, public facilities or retail hubs. Most important is how these complex components are orchestrated and fit together through urban design. Attention to detail is key, such as how buildings hit the street. Are there blank walls or fine grained textures and a diverse assemblage of coherent pieces?

Done well, people are encouraged to mix and to talk across social boundaries and this enables community bonding. This happens at the smaller neighbourhood level as well as the broader arena. Living in the city should feel as if one is at the centre of a communications web starting from intimate surroundings to the ability to be part of a wider world. Connection too means relating to the past and heritage of our city as well as its possible futures.

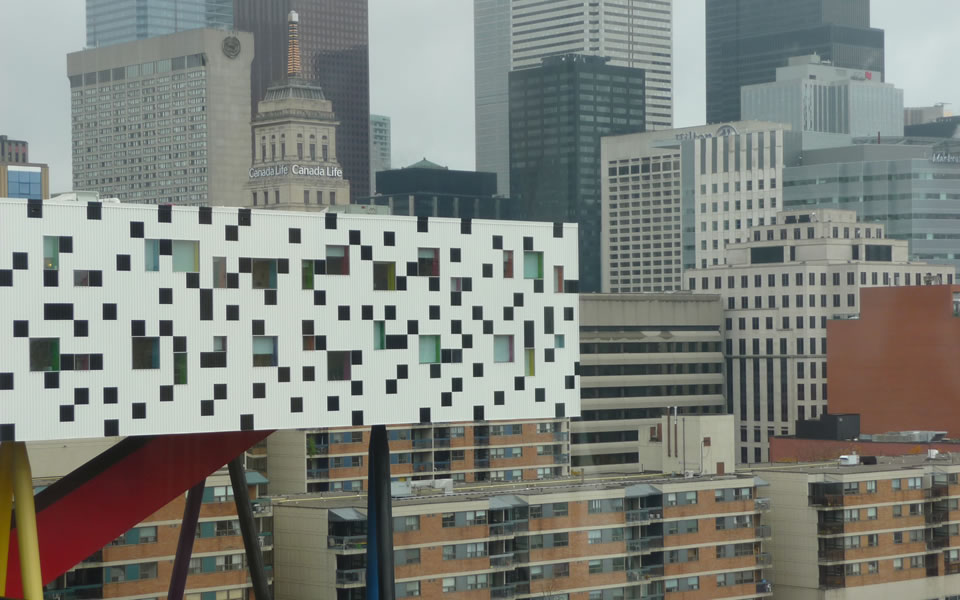

The great city avoids the trap of homogenous development and understands the power of distinctiveness. A city is a designed artefact with its cultural values embedded and enmeshed. That is why cities look different across the world. Yet this is changing dramatically as the skylines or housing estates the world over look similar. The unique is in rapid decline. If you leave out the signature buildings you cannot tell Sao Paolo from Tokyo or Shanghai, Mumbai and Johannesburg or Dubai from Toronto or Milan. Architects may try to build iconic structures but very few remain in the mind or have a lingering effect. Their traveling circus moves from place to place and seeks to create distinctiveness through outrageousness. But mostly what we see is bland and monotone.

Every facet of the city speaks to us emotionally from the streets we travel on to its buildings, private and public, its housing and its sense of organizing its space. It is a dense agglomeration of unremitting physical infrastructures. Considered urban design that makes this become sensible, legible and liveable. The city is a toolbox of elements with primary and secondary streets forming the central frame, with pocket parks and the public realm leavening the density, and corner buildings firming up the structure. Yet the great city is created by more than a hardware- focused culture of engineering; instead it thinks, plans and implements holistically.

Its choices are framed by firm principles. Human scale is one norm rather than the more monumental. A pedestrian focus is another rather than making the car more important. This shapes priorities such as between public or private transport. Then there are balances such as the right mix between the grandiose and domestic; the judgement, starkly put, is whether a city wants one icon or 100 smaller things done well.

The city is a mix of the planned and unplanned and the challenge for planners is to assess how much left to leave to serendipity and chance and what needs to be guided through a regulations and incentives regime. The hustle and bustle markets and their independent stall holders are best left alone, whereas major developer interventions creating a glitzy mall may need a firm hand to ensure public interests are maintained.