Smart means clever, quick witted and intelligent and is now a word in danger of over-use and exhaustion especially in the context of cities. The ’smart city’ concept has corporate origins as IBM, Cisco and Siemens and others found a new market for their digital services. Since then public interest entities have been trying to wean the focus away from purely technological opportunities to how clever devices can help people to become smart citizens – citizens that are aware of global priorities from climate change to community bonding. In essence they want ‘smart city’ to mean ‘making the most of a city’s human, technical and ecological resources to increase the quality of city life’ or ‘doing more with less’ and so being clever in the process of using ICT. In addition the inherent promise of digitization and GPS technology is that we can re-create some of the social bonds, connections and interactions at a more local level that we have lost and make our lives more seamless and convenient.

Here the human being rather than technology is placed at the centre of thinking by emphasizing how the ‘smart citizen’ and their abilities, aspirations and anxieties can foster a better world. Eurocities summarizes well the perspective from a public interest view: ”Becoming a smarter city is not an end goal, but a continuous process to be more resource efficient whilst simultaneously improving quality of life”. Crucially the positives of the smarter cities debate is how it has turbo-charged the open data agenda so shift cities towards openness in terms of data, interfaces, and platforms. It is openness that allows citizens to be and become fully fledged participants as users and as innovators in making urban life more convenient. Smarter cities should be inclusive places that use technology and innovation to empower, engage with and capitalise on citizen participation. Engaging citizens goes beyond the uptake of technology. There are no one size fits all solutions: becoming smarter will mean different things to different cities. Most of all, it is crucial to involve people in the process: there can be no smart city without smart citizens. “Smarter cities should be inclusive places that use technology and innovation to empower, engage with and capitalise on citizen participation. Engaging citizens goes beyond the uptake of technology.

Yet we talk of smart cities and we have the technologies to make them happen. But many would argue that have we not advanced enough. Rick Robinson, a leader in smart thinking and IT director for Smart Data and Technology engineering company Amey, provides an insightful overview of the movement’s shortcomings and what can be done to address them.

This brief collection of links to projects across the globe first appeared in the New York Times voices site. ‘Smart City’ has become a buzz phrase, but what does it mean? The goal of a smart city is to invest in digitally-driven technologies to help make cities more efficient and responsive to citizens’ needs. This city is full of sensors that communicate. The sensors monitor pollution levels, bus locations and parking spaces. They can also tell garbage collectors which bins are full and adjust lighting levels depending on whether people are present.

While the digitized city has the potential to improve the quality of life in cities by making them more citizen-centric, it also carries risks. Giant technology companies like Cisco and Siemens are major drivers in this movement and stand to gain enormously. Who will own all of this new data? And who will benefit the most?

The digitized city is already with us, but it needs a jointly created vision of where to go next.

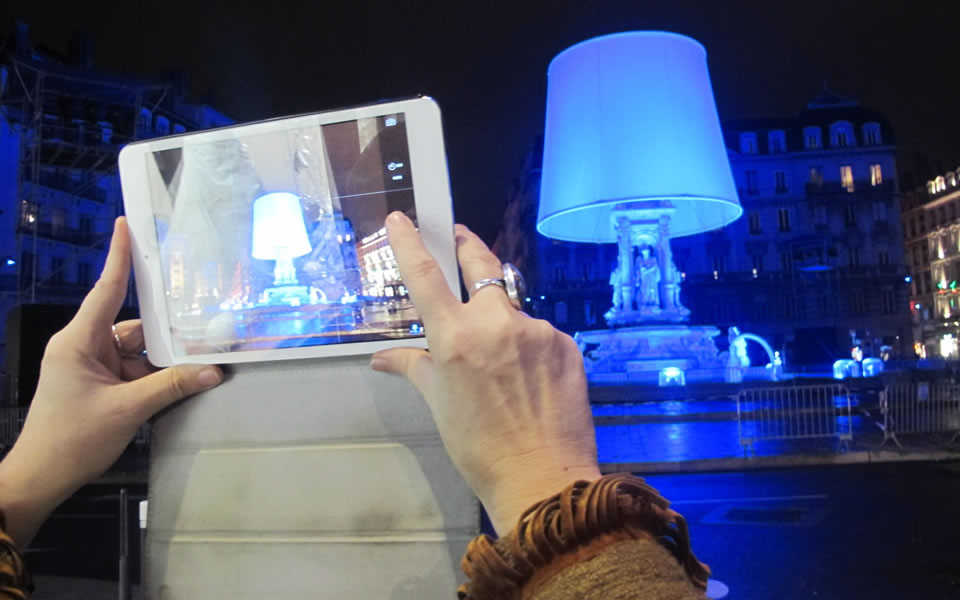

Amsterdam has been a leader in innovation for centuries and has been recently voted European Capital of Innovation. Innovation is in the city’s DNA. The constant fight against floods has forced citizens to collaborate, resulting in a society that relies on creativity and teamwork. That same spirit is evident today in the Amsterdam Smart City (ASC) collaboration -- a partnership between companies, local and central governments, academic institutions and the people of Amsterdam. More

In Barcelona, digital chips in the asphalt and on lampposts monitor a range of variables—down to the number of selfies posted from a particular corner. No wonder it has been rated the “smartest city in the world.” That leaves some of its citizens worried about the prospect of a new Big Brother. More

The smart city movement is driven both by tech companies like Cisco, IBM and Siemens but also by cities themselves, many of them in poor countries, who need to save money and be more efficient. The most ambitious smart city initiative underway in the developing world is taking place in India. But is the infrastructure of these cities shifting into private hands? While the government will provide part of the funding, the bulk of it will have to come from private investment. More

North America has many smart city initiatives. Some of the more notable examples include Boston’s solar powered benches that power gadgets and monitor air quality; San Francisco’s charging stations for hybrid and electric cars; New York’s interactive platform that integrates information from government programs, local businesses, and New Yorkers to provide knowledge to anyone, anywhere, anytime, on any device; and Seattle’s electric meters that give users accurate readings of their electricity consumption so they can save energy. More

Smart city initiatives can be isolated and fragmented, lacking a broader smart ecology. It is often in smaller cities that you can undertake comprehensive experiments to bring all the pieces together. In Belgium, Antwerp’s City of Things project is exceptional. Launched in December 2015, it connects the city’s 200,000 citizens with a massive amount of smart devices spread over the city. For example, the city’s postal trucks are now equipped to monitor the state of the city’s environmental health. More

Masdar City, in United Arab Emirates, is a good example of how the dream of sustainable, smart cities can go wrong. Ten years after the zero-carbon desert hub was conceived, planners say its clean tech goals were unrealistic. More

Openness is the over-arching quality that allows places to adapt to changing circumstances to detect and grasp opportunities or to avert a crisis. Yet for centuries information was closed and closely guarded by the state or city as a tool of power highlighting the suspicion that there is something to hide. Authorities provided access to information on a need-to-know basis rather than assuming citizens want to know or would have the right to know rather than the privilege to know. It is astonishing how many places still remain reluctant to give out data that belong to citizens since it is their taxes that is paying for information.

The near monopoly on creating and giving out information that public data providers and statistical offices have held is now broken. Yet ironically the desire of progressive cities to open up their data is helping to break down their own strong positions as activists, as the business world and others embrace the resulting digital opportunities.

The communications revolution has played its as everyone has access to knowledge on their devices and is able to be an editor of their own media. The combination of principle and technology has made transparency possible and there is no principled excuse for hiding - formerly you could claim a technical barrier and say: ‘it is difficult to open data’. Openness rather than secrecy should be the new default. This triggers new forms of governing as cities respond to greater transparency.

Now we are moving to having a ‘right to data’ and the ‘right to be protected from data collection about me’, but more needs to be done as there is no even playing field. It is fine that businesses innovate with open data, but models need to be explored so that the benefits business create, beyond taxation, are more evenly shared with citizens.

Good open data tells us about the state of the city as well as the pulse of the city and so helps co-create solutions to problems, new services or makes life more seamless. Smarter cities use new tools such as public calls for problem solving, or set up living labs and experimentation zones or mechanisms to integrate citizen input in urban planning. The first city to grasp the potential of the connectivity and data revolution was Washington, DC with its ‘Apps for Democracy’ project of 2008. This was a game-changer and in effect launched the open data movement. This inspired cities like Helsinki, Amsterdam, Barcelona and others to follow suit from 2010 onwards. My Data 2016

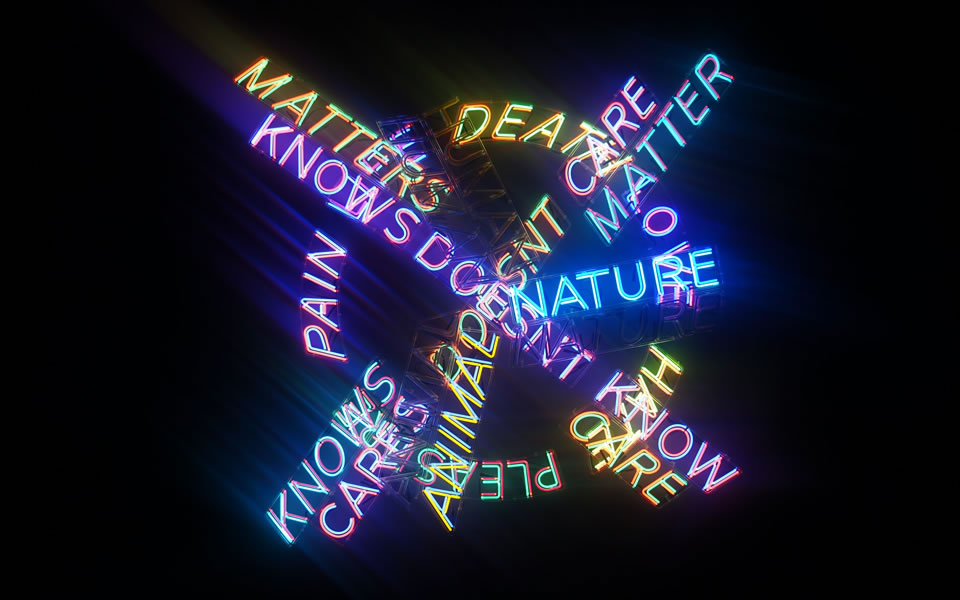

The digital is opaque. Algorithms behind the scenes control everything we do on and off the web. Algorithms are a self-contained step-by-step set of instructions that with increasing sophistication become automated reasoning that mimic our minds. Lifeless formulae they show no emotion and have no truck with special circumstances. They cannot consider you as a living being instead you are yourself more a chunk of mathematical signals and bits.

Spookily they are closely guarded commercial secrets. Getting a loan – an algorithm looks at your bank records and decides without human intervention. Dating – an algorithm sifts through characteristics to give you a perfect match. What books you might read or films to watch, what you might buy, all can be calculated and it is cookies that help this process. These algorithms help sift through data ultra-fast to determine whether you are a security threat, while also can be used to spy on you. They are ‘the maths that help computers decide stuff’. They are invisible computations that increasingly determine how we interact with the electronic world. No wonder we need to know as a matter of public policy.

The web needs to explain itself and a role of public entities is to make its processes transparent as well as find ways to make the invisible visible as only then can people participate and engage as capable, empowered citizens.

Crucially for city decision makers the power of big data and its associated algorithms lies in its capacity to move from descriptive to predictive to prescriptive analytics as well as doing data analysis in real-time. Seen as the final frontier of analytical capabilities it automatically synthesizes data with mathematical and computer sciences to make both predictions and then to make recommendations for decision making.

Descriptive analytics looks at past performance and trends, predictive analytics tries to assess the likelihood of what will happen and the prescriptive tells you what to do. Where does that leave autonomous judgement, what then is the role of intuition or insight, what about subjective factors and feelings?

There is IQ, EQ, CQ and now DQ. That is the intelligence quotient, emotional intelligence, called EQ, cultural intelligence called CQ and now the digital quotient DQ – the digital savviness of a business, place or city.

There are several ways of measuring how well your city is doing and Dublin’s Digital Masterplan launched in 2104 for me is the best. It was the first comprehensive and pioneering initiative whose Digital Maturity Scorecard (DMS) focused on the whole urban eco-system. Unfortunately, the city has put this holistic evaluation system on hold even though it would put Dublin at the forefront of digital thinking. It has scaled its plans back to focus more on tactical issues like delivering sensors for lighting, mobility, pollution and so on.

Yet the DMS provides the necessary broad-based conception that cities require to assess where they stand digitally and what they need to do. It defines six layers of digital activity that the city must build up to international and best practice standards in order to become a truly Digital City with a roadmap to match as follows:

Digital city governance to include: vision, strategy and management processes as well as an open innovation culture and novel procurement policies. The building ubiquitous city networks element includes interconnected, intelligent digital capacities. The leveraging urban data component measures platforms, storage and analytics as well as progress on security and privacy issues. Fostering digital services capabilities looks at interoperability or levels of participatory design. Digital access and skills proficiency evaluates research capacity and digital inclusion. Finally city impact realisation assesses behaviour change, performance management or financial and non-financial returns.

Actions pursued as part of the Digital Masterplan relate to one or more of six digital city service domains which impact on quality of life in the city region: economy and innovation; community and citizenship; culture and entertainment; movement and transport; urban places and spaces; environmental practices. Within each domain there are also sub-elements within there are good practices that cities can aim for.

The scorecard looks at maturity on a scale of one to five. One is ‘ad hoc’ an unmanaged digital platform with little integration and insufficient skills. Level two is ‘Basic’ with a developing platform that has pockets of digital service innovation and limited citizen engagement and varying degrees of connectivity. Level three is ‘intermediary’ which is a somewhat progressive platform with citizen feedback loops and quadruple helix thinking embedded and a city data platform. Level four is ‘advanced’ with a proactive digital platform, integrated access, self-regulating intelligence and pervasive citizen participation. Level five is described as ‘optimising’ and digitally savvy, with ubiquitous networks, bottom up entrepreneurship and shared governance.