Most things have been reinvented: how we do business, how we build cities or how we entertain ourselves and of course technology has moved apace in gigantic leaps enabling to connect across the world in completely unforeseen ways. Yet our forms of representative democracy have remained largely the same for hundreds of years. Essentially we vote for politicians to speak on our behalf every four years with little involvement in between, even though substantial efforts are made to consult citizens on local plans or in some countries to hold referenda on major issues.

Clearly this is not enough as low participation in voting show. Cities need to explore new ways of communicating with citizens so engagement with the civic can be reignited and policies can be co-created. Here the open data movement is one important initiative in making hitherto hidden information freely available as are new ways of decision making such as citizen juries or other forms of participative democracy from on-line voting to town hall meetings.

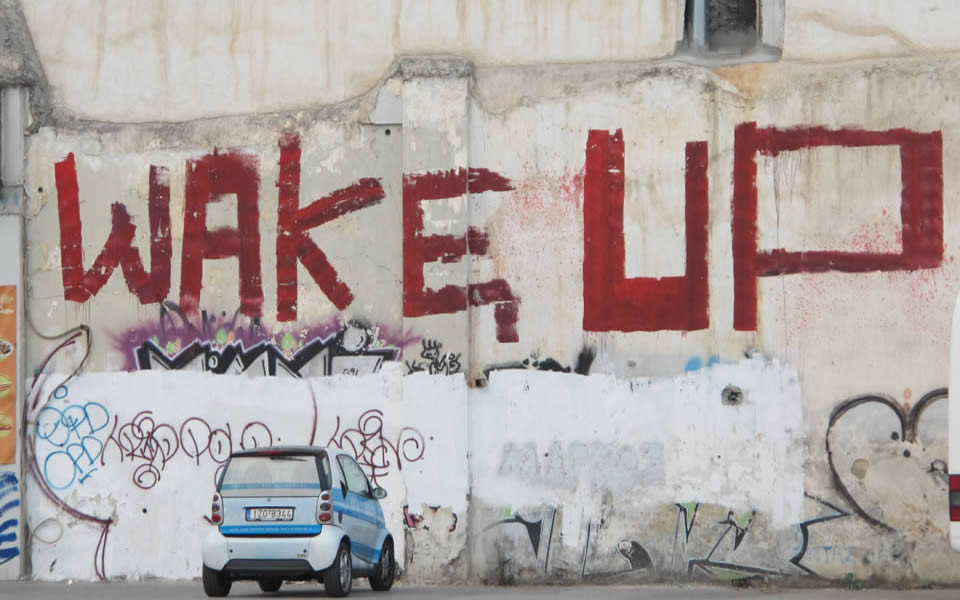

There is a thirst for re-engagement even though many feel powerless to effect change and social activism remains as vigorous as ever as people try to take more control rather than being victims of circumstance. It has taken on new forms of which harnessing the social media is the most prevalent. There is a need for a new settlement to build greater consensus between citizens and those who make decisions on their behalf.

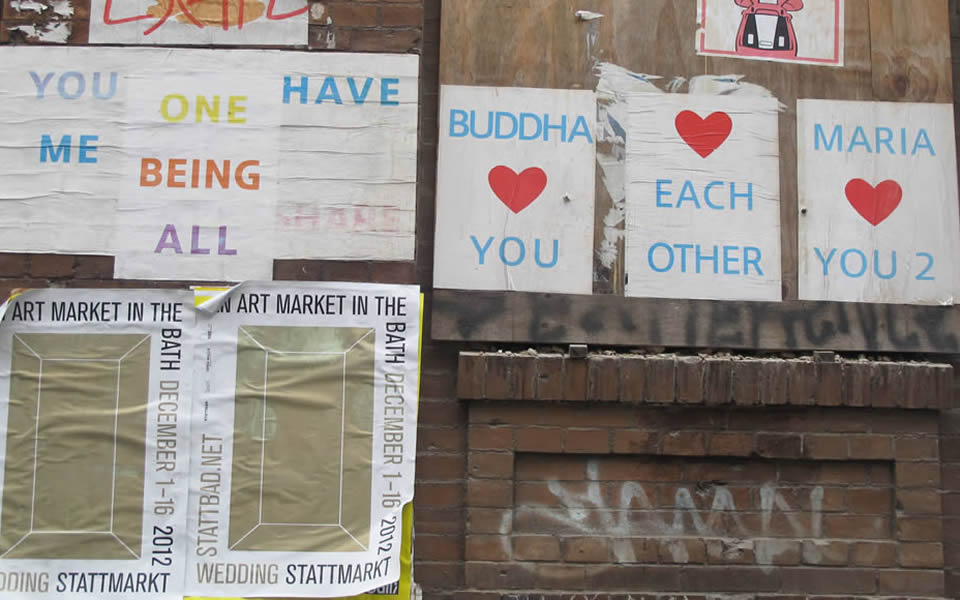

There is a demand for a reinvigorated public and shared commons. This is a social ethos that argues against our increasingly tribal and self-centred public culture based on celebrity culture and hyper-activated consumption. It argues against places where everything is privatized and to do anything has a price attached to it. It fosters amongst other things spaces and places from streets where you can sit and watch the world go by, to pocket parks to libraries that are accessible, free, and non-commercial.

It encourages a style of life where we voluntarily give time to our neighbours and our city from small civic gestures to those on a grander scale. Such places provide opportunities for us to come together as one so that we feel as citizens whether these are celebratory events or moments of self-reflection. This fosters a sense of belonging and commitment.

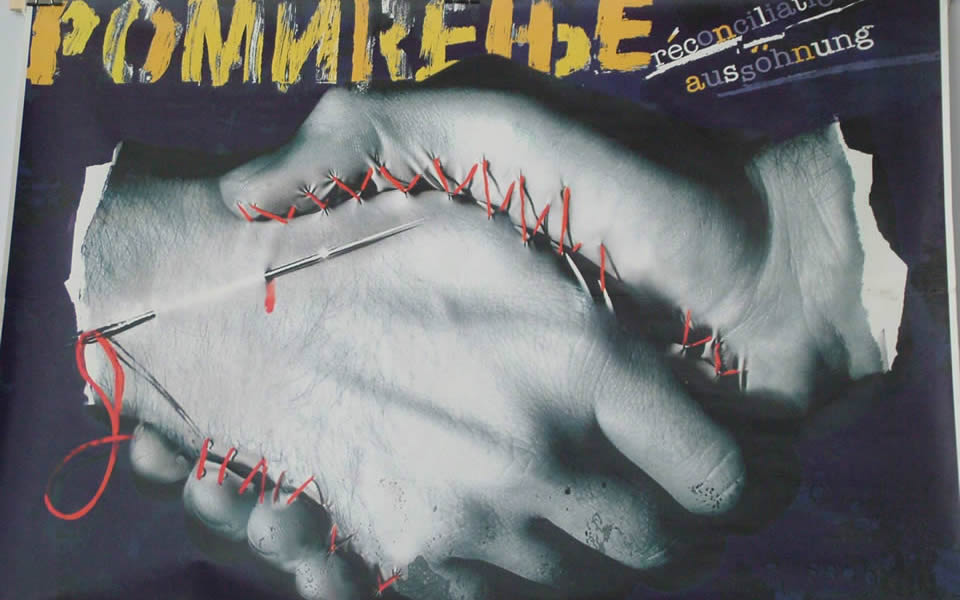

Cities only work well when there is give and take and where a culture of entitlement is reduced. Places underpinned by this ethos can help retrofit conviviality and the habits of solidarity so helping to nurture our capacity to bond and to build social capital. Crucially there is a contrast; with financial capital the more you spend the less you have, but the more you spend on building social capital the returns become ever greater.

In time the urban civility this fosters encourages individual and collective gestures of generosity. In turn a self-generating process is created leading to a virtuous cycle fostering a participatory culture.

This commons has a virtual mirror where access to information and knowledge is easily available and where more open public and private data provides us with the capacity to create an evolving and enriching public commons.

Creative city making seeks to address the escalating crisis cities face that cannot be solved by a business as usual approach, including the challenge of living together with great diversity, addressing the sustainability agenda and how cities can rethink their roles and purpose in a changing world to survive well economically, culturally and socially and to manage increasing complexity.

It argues that curiosity, imagination and creativity are the pre-conditions for inventions and innovations to develop as well as to solve intractable urban problems and to create interesting opportunities. Unleashing the creativity of citizens, organizations and the city is an empowering process. It harnesses potential, it searches out what is distinctive and special about a place and is a vital resource. It is a new form of capital and a currency in its own right. Creativity has broad based implications and applications in all spheres of life. It is not only the domain of artists or those working in the creative economy or scientists, though they are important. It includes too social innovators, interesting business people or bureaucrats or anyone who can solve problems in unusual ways. Cities need to create the conditions for people to think, plan and act with imagination.

To make this happen requires a different conceptual framework. For too long there has been an ‘urban engineering paradigm’ of city development focused on hardware. ‘Creative city making’ by contrast emphasizes how we need to understand the hardware and software simultaneously. In turn this effects the ‘orgware’ of a city, which is how manage the city under these new conditions. Today the personality of many cities is their ‘culture of engineering’ whose attributes and mindset are both positive and negative. It is logical, rational and technologically adept, it learns by doing, it advances step by step through trial and error. It is hardware focused. It gets things done. Its weakness is that this it can become narrow and inflexible and forget the software aspect concerned with its activity base, how a place feels and its capacity to foster interactions.

Cultural literacy is now a necessary, vital skill as important as numeracy, normal literacy, or understanding the laws of physics, especially now that cities are far more diverse. Without it we wander as if we had no sight or language. Cultural literacy is the ability to read, understand, find significance in, evaluate, compare and decode the local cultures in a place. This allows one to work out what is meaningful and significant to people who live there. We understand better how the local identity is made up and what its potential and problems are and how these may be addressed.

All our bigger cities are becoming much more diverse in their make-up. Multiculturalism as a planning concept and a policy is the predominant approach acknowledges these differences. It highlights the need to cater to diverse needs. Interculturalism goes one step further and has different aims and priorities. It asks instead ‘what when we are sharing a city can we do together across our cultural differences’. It recognises difference, yet seeks out similarities. It highlights that in reality most of us, when we look deep, are hybrids and so downplays ideas of purity. It stresses that there is one single and diverse public sphere and it resources the places where cultures meet. It focuses less on resourcing projects and institutions that can act as gate-keepers and instead encourages bridge-builders. In so doing it does not consider that there is a cosy togetherness. It acknowledges the conflicts and tries to embrace, manage and negotiate a way through them based on an agreed set of guidelines of how to live together in our diversity and difference.

In sum it goes beyond a notion of equal opportunities and respect for existing cultural differences in order to achieve the pluralist transformation of public space, institutions and our civic culture.

All cities talk of sustainability. Every vision statement mentions combating the effect of climate change, some even wish to become carbon neutral.

Taking a helicopter view of cities worldwide there are many good initiatives, but rarely are all the good initiatives found in one place. Also few cities make the hard planning choices to counteract an economic dynamic, spatial configurations and physical forms that continue to make cities less sustaining in every sense.

Lurking on the horizon are severe threats to urban life as we know it of which Storm Sandy in New York and Katrina in New Orleans or the Australian bush fired threatening cities are the first harbingers. It will not only be coastal cities that are affected.

Cities have been insufficiently courageous or imaginative in helping to change behaviour patterns. The eco-city needs a different operating system. Nor have cities developed a new environmental aesthetic that inspires people to think afresh. Eco-conscious places may look and feel unlike the cities we know.

360° thinking has not embedded itself into decision making circles so that it becomes a new common sense. As a consequence the regulations and incentives regimes are not clever enough to drive change. The necessary and dramatic retrofitting process still has a very long way to go even though there are vast economic opportunities from being part of the 4th lean, clean, green industrial revolution. ‘Cradle to cradle’ decision making remains far off.

The cities we have and continue to build make us unhealthy. Urban planning that helps makes you healthy by simply navigating the city in day to day ways has not imbued planning disciplines. This would focus on walkability, ease of access and pleasurable environments.

We know about unhealthy urban planning. Rigid ‘land use zoning’, which separates functions and gets rid of mixing uses such as blending living, working, retail and fun; ‘comprehensive development’ that can do initiatives in one big hit so often losing out on the fine grain, diversity and variety; ‘economies of scale’ thinking with its tendency to think that only the big is efficient. Equally producing bland conveyor belt projects and lastly the ‘inevitability of the car’ which can lead us to plan as if the car were king and people a mere nuisance. Walkable cities give you time and space to experience the city in visceral ways as part of being healthy is sensory satisfaction.

A healthy place is one where people feel an emotional, psychological, mental, physical and aesthetic sense of well-being; where doing things that make you healthy happen as a matter of course and incidentally and not because you have to make a big effort or have to go to the gym. A healthy place throws generosity of spirit back at you. This makes you feel open and trusting. It encourages us to communicate across divides of wealth, class and ethnicity. It makes for conviviality. And having trust is the pre-condition for learning, creativity and innovation.

The aesthetic view of life covers not only about beauty and visual attractiveness, but all the senses: seeing, hearing, smelling but also space, mass, volume, time, colour, light, pattern, order, information. It is an inclusive perceptual system. The lived urban experience comes from a circular sensory cycle with emotional and psychological impacts.

Our personal sensory landscape is shrinking, precisely at the moment when it should broaden. We sense our worlds through increasingly narrow funnels of perception. Living in an impoverished mindscape makes us operate with a shallow register of experience and understanding about what is important for our cities to survive well. We have more sensory bombardment, but have lost the art of appreciating the varied sounds, smells, the texture and quality of materials and the look and feel of the city and its component parts. There is distraction, loss of attention, concentration and focus. Sensory appreciation builds the knowledge upon which our worlds are built. This effects beliefs, choices and our priorities for change.

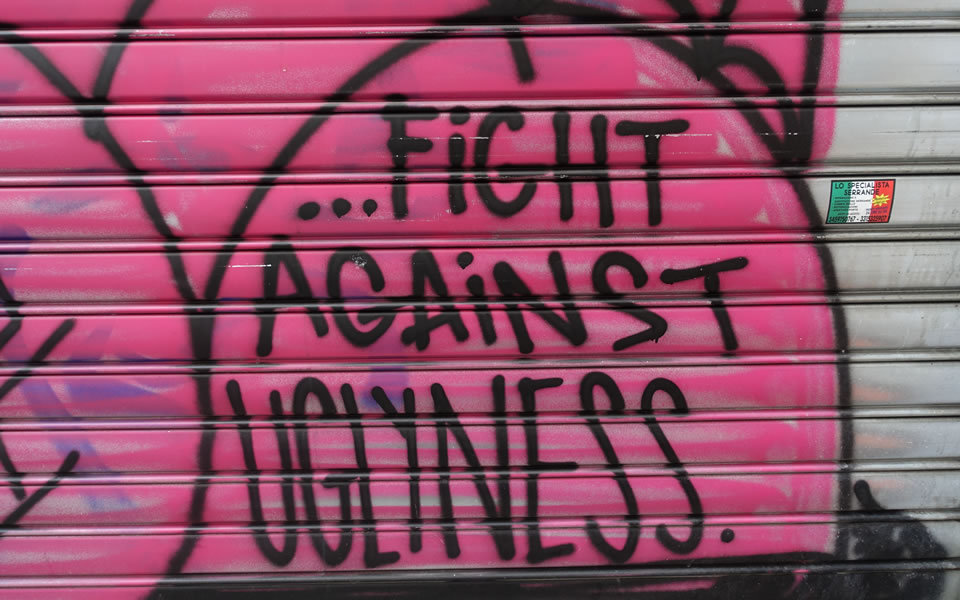

There is a desire in many to take more control of our sensory environment, rather than becoming passive consumers or victims of its effects. Whether we allow commerce and the media to trespass on our senses will be one of the crucial battles in defining how our cities evolve in the future. Yet the urban policy world has insufficiently understood the power and potential of the senses. The contrast between everyday sensing of the city and how policy makers usually describe cities as lifeless beings is stark. A greater understanding of the importance of environmental psychology is crucial. This focuses on the interplay between people and their surroundings and the degree to which it creates stress or feels restorative.

There is an aesthetic imperative as every physical structure has an aesthetic responsibility to the environment and people in which it sits. Environmental psychology shows these have negative impacts and can lead to depression or disease. Remember the pinpricks of ugliness spilling out from horrible buildings, misplaced urban design or insensitive infrastructures throughout their lives.